(From 2021)

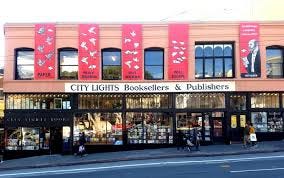

With the passing of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a significant guardian of San Francisco’s post-war bloom has left us. For me, like so many others, his City Lights bookstore was on my bucket list in 1971 when I arrived here. I saw Ferlinghetti there on several occasions. He even rang me up once.

Over the years, I’d meet up with writers whose pieces I was editing at City Lights and we would migrate to one of the nearby cafes -- Vesuvio or Trieste -- to work over coffee. It made us feel cool. The spirit of the Beats from the 50s permeated everything we did as our version of an alternative culture made up of the hippies of the Haight and the radicals of Berkeley went seriously viral.

In 2001, I edited an interview of Ferlinghetti conducted by my friend Ken Kelley. The poet was in a nostalgic, unhappy mood, as he watched gentrification drive high rents that made the lifestyles of poets, artists, freelance journalists and the rest of us so much more difficult than it had been in his younger years.

His spirit was generous -- he wanted us to have the experiences that had inspired him.

By 2015, I was at KQED when we interviewed him again, and he expressed his ongoing disappointment with how the city had seemingly abandoned its old spirit to become an elite playground for rich people.

But change is inevitable and the good old days were never quite as good as our memories suggest. There was a lot of poverty in San Francisco, especially among minorities back then and there still is, and I’m afraid that all of us who identified with the beatniks, hippies and radicals haven’t collectively been able to change that in any lasting way.

None of that is to disparage the spirit of Ferlinghetti. He probably accomplished more than he realized by remaining a symbol of an alternative way to live life and also by simply living so long. Until Monday he was still among us, although most current residents of his city probably didn’t know that. Now he is gone, everybody knows that.

That’s how it is with death. You don’t know what you had until it is gone.

***

Among the obscure but extremely important news stories this week is a report on the continuing loss of fertile topsoil in the part of the country where I grew up -- the upper Midwest. Scientists have long since established that this devastating loss is due to modern industrial farming methods.

The use of chemicals, both fertilizers and pesticides, is largely to blame. These kill off beneficial creatures that keep the soil healthy, including earthworms that aerate the soil -- keeping it moist and oxygenated. Before petrochemicals, multiple microorganisms also contributed to this vital process.

Mono-cropping plays a deleterious role, as does the use of heavy machinery, which compacts the soil. These various factors increase the runoff that causes rainfalls to carry soil away -- permanently.

Of course, these mechanical and chemical techniques also boost overall food production, helping to feed the world.

By contrast, organic farming methods rely on time-tested techniques like crop rotation, composting, mulching, biological pest and weed control, and diversity to preserve and renew topsoil during the farming process.

Organic farming is time- and labor-intensive. It yields food that is more local and seasonal in nature, healthier and often much tastier than the industrial produce available in your typical supermarket. But the overall output is lower.

Also, the fruits and vegetables grown this way may have some scarring and not be as pretty as their industrial counterparts; they also are more expensive, but we as consumers have to be willing to shoulder these tradeoffs for a healthier, sustainable food system that will last into the future.

Again, the headline is that we are losing the topsoil that enables this alternative lifestyle. Death isn’t funny that way. You don’t know what you had until it is gone.

HEADLINES: