(This is the latest of 43 conversations I have had with a young Hazara man in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. His identity is confidential for obvious reasons.)

Dear David:

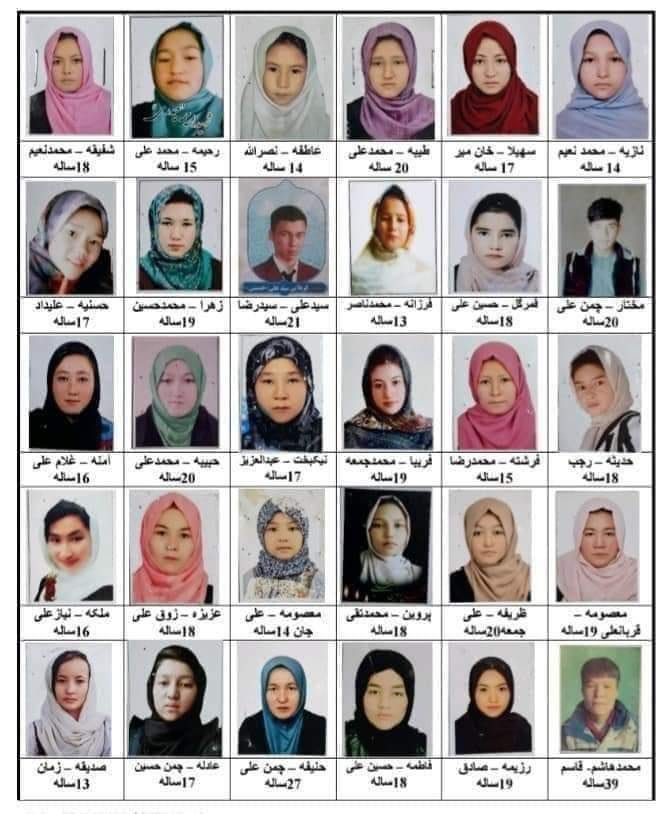

Friday was a very sad day for me and for the Hazara people. Dozens of innocent teenage students were slaughtered in an educational center in Kabul and dozens more were injured. Most of the victims were girls. They all were Hazara.

It also was personal. Two of my brothers and one sister studied mathematics and physics courses at that very center last year.

Hazaras in general are treated badly in Afghanistan, as we are looked down upon by other ethnic groups, especially the Pashtuns who dominate the Taliban. Hazara parents place a very high value on the education of their children – both boys and girls. They see no reason for girls to be excluded from going to school.

Therefore, during the 20 years prior to the Taliban takeover, Hazara children (including me) flocked to the schools. We studied hard and went as far as we could in our education. Some, like me, have college degrees and are interested in further academic careers. But there are no opportunities for us here in this forgotten country.

Among the Pashtuns, those who support the Taliban consider public schools and universities a danger to their beliefs. They send their children to Madrasas (religious schools) instead.

Since they feel threatened by secular education, and also by the relatively trivial religious differences between the fundamental Sunni sect of Islam they follow and the Shia sect of the Hazara, they ignore the many ongoing attacks on the schools where Hazara children study.

Most of the worst of these attacks, including Friday’s, have taken place in Dasht-e Barchi—a majority Hazara district in the western part of Kabul. On April 19, 2022, two blasts occurred at the Abdul Rahim Shahid high school, killing six civilians and injuring dozens.

On May 8, 2021, as teenage schoolgirls and young women were leaving the Sayed Ul-Shuhada high school in Kabul, multiple improvised explosive devices were detonated, including a car bomb parked in front of the school. The attack killed at least 85 people and injured at least 216 others—mostly girls and women.

On October 24, 2020, a suicide bomber detonated explosives near the exit of the pre-university education center Kawsar-e Danish. The attack killed 40 civilians and injured 79 others.

On August 15, 2018, a suicide bomber detonated explosives inside a classroom of the college prep center Mowud, killed at least 48 civilians, and wounded 76 others.

All of these victims were documented by the UN. All of the victims were Hazaras between 15 and 20 years old – students at the educational centers.

It seems there will be no end to the massacres of our people. There is no authority for us to complain to. The Taliban authorities do nothing. No one is ever tried, convicted or punished for these attacks.

This is genocide. But it also reminds us that we Hazaras are a people without a country. And that the international community doesn’t care and won’t come to our aid.

Our tears will simply blow away on the wind.

LINKS:

Dozens dead and injured after suicide bomb blast at educational center in Kabul (CNN)

Afghanistan: Kabul blasts signal utter failure of Taliban to protect minorities (Amnesty)

Bikes are everywhere in Kabul since the Taliban takeover. But who's not cycling? Women (NPR)

Hurricane Ian’s Staggering Scale of Wreckage Becomes Clear in Florida (NYT)

Ron DeSantis changes with the wind as Hurricane Ian prompts flip-flop on aid (Guardian)

DeSantis, Once a ‘No’ on Storm Aid, Petitions a President He’s Bashed (NYT)

Florida death toll rises from Hurricane Ian (Axios)

Far From the Coast, Ian Leaves Flooding and Damage Across Florida (NYT)

After Ian, the effects in southwest Florida are everywhere (AP)

Putin announces illegal annexation of Ukrainian regions, pledging people there will be Russian ‘forever’ (CNN)

US hits Russia with sanctions for annexing Ukrainian regions (AP)

Russian forces in Ukraine were on the verge of one of their worst defeats of the war even as President Vladimir Putin was due to proclaim the annexation of territory seized in his invasion. The pro-Russian leader of occupied areas in Ukraine's Donetsk province acknowledged his forces had lost full control of Dobryshev and Yampil villages, leaving Moscow's main garrison in northern Donetsk half-encircled in the city of Lyman. (Reuters)

‘Putin Is a Fool’: Intercepted Calls Reveal Russian Army in Disarray (NYT)

Finland said it would close its border to Russian tourists, shutting off the last remaining direct land route to the European Union for them as thousands of Russians seek to avoid conscription. (Reuters)

Russian pipeline leaks spark climate fears as huge volumes of methane spew into the atmosphere (CNBC)

What if We’re Already Fighting the Third World War? (New Yorker)

S. Korea, US and Japan hold anti-N. Korean submarine drills (AP)

Britain’s Gamble on Tax Cuts Has Economists Warning of Past Mistakes (NYT)

Ginni Thomas falsely asserts to Jan. 6 panel that election was stolen, chairman says (WP)

House passes government funding, averting shutdown threat (Politico)

Few Senate lawmakers can say with confidence who will control the chamber next year. Democrats are hoping to defy history. Republicans are betting on economic issues, and with the current 50-50 split, the GOP only needs to pick up one seat to win control in January. One factor that could shake up the race for Senate control is next month’s scheduled candidate debates in Pennsylvania and Georgia. Meanwhile, House Democrats are optimistic the party could pick up seats in November. [HuffPost]

Six Republican-led states are suing the Biden administration to block a plan to forgive student loan debt for tens of millions of Americans, accusing it of overstepping its executive powers. This is the second challenge to Biden's student loan forgiveness plan this week. [AP]

Threats to water and biodiversity are linked. A new U.S. envoy role tackles them both (NPR)

The Pandemic’s Legacy Is Already Clear — All of this will happen again. (Atlantic)

Biden Issues Urgent Warning For Americans To Decide What To Be For Halloween Now (The Onion)