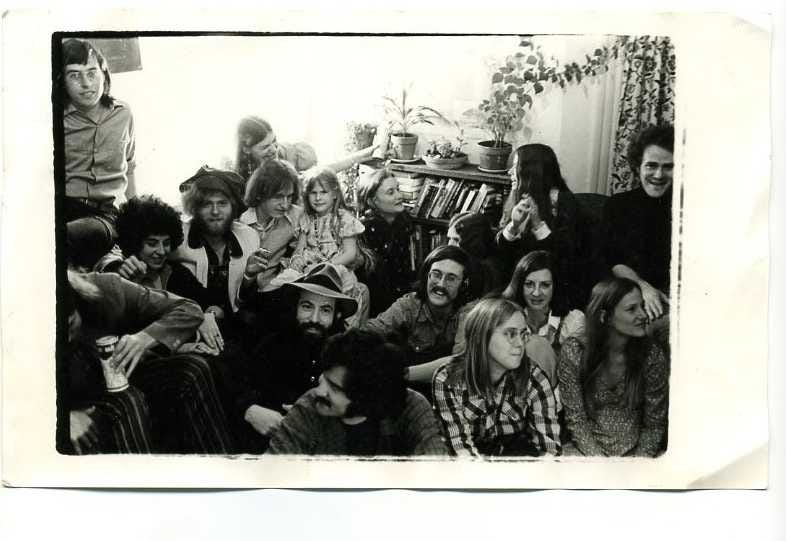

(Ann Arbor expats gathered in my apartment in the Fillmore District of San Francisco in the early '70s.)

I was born in Detroit two years after the end of World War II. My family moved into one of the city’s expanding suburbs, Royal Oak, amidst a cluster of other families that consisted of returning soldiers, wives and boys and girls named David, Susan, Bill, Bob, Jim, Mark, Bonnie, Nancy, Kathy, Fred, Peter, Carole, Paul, Diane, Mary, John, and so on and so forth.

We were the leading edge of the Baby Boom generation -- a cohort so large that we broke every institution we encountered. When we got to school, there were never enough classrooms, chairs, desks, books, or other resources. Teachers suddenly had to handle many more students at once than had previously been the case.

When we reached our teens, there simply was not enough beat in the music that our parents and older siblings enjoyed. Thus, the mass market for rock and roll was born.

Meanwhile, the political economy of the nation newly victorious in the second war of wars dictated that America become an empire, as all conquerors since time immemorial have done.

As we grew up, America's capitalist empire -- imperialistic, arrogant, and driven by opposition to communism -- spread globally.

We were served books like "Our Friend the Atom," a distinctly propagandistic reader that was our government's attempt to convince us, years before we could vote, of the rightness of its policy to develop nuclear weapons to protect us from the Russians, Chinese, and other socialistic foreigners.

Much of the rest of my generation's story is written contemporaneously in music, in poetry, in film, and in our collective memory. Confronted with the worldview that our fate was to conquer the world, many of us rebelled, begging to differ.

We opposed the war in Vietnam. We marched in support of the civil rights movement. We launched the modern women's liberation movement and the gay liberation movement. We smoked dope and dropped acid and danced in the streets. We flocked to the nascent environmental movement.

We were idealists and cynics, hippies and radicals. For our guides, we had Dylan and the Beatles, the Stones, and so many more. The music always reflected us as the ragged edges of a churning chainsaw that sliced our way through society trying to establish a new way of being.

Did we succeed in doing that? Probably not. Progress requires struggle and there have been many setbacks. The culture wars rage. It often looks bleak but three-quarters of a century later, many of us are still trying.

(I published the first version of this essay in 2006.)

HEADLINES:

Upside-down US flag flew at home of Justice Samuel Alito after 2020 election (NYT)

What Israel’s strategic corridor in Gaza reveals about its postwar plans (WP)

Aid for Gaza will soon flow from completed pier project, Pentagon says (Politico)

Hezbollah introduces new weapons and tactics against Israel (AP)

A Free, Prosperous, and Secure Future for Ukraine (US State Dept)

As Russia Advances, NATO Considers Sending Trainers Into Ukraine (NYT)

Donald Trump wants to control the Justice Department and FBI. (Reuters)

Man convicted of attacking ex-Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband with a hammer sentenced to 30 years (AP)

Detroit sees first population growth since 1957 (Detroit News)

Major cities whose populations fell during the coronavirus pandemic are recovering — although some still haven’t surpassed pre-pandemic numbers. (WP)

70 years ago, school integration was a dream many believed could actually happen – it hasn’t (AP)

America is in the midst of an extraordinary startup boom (Economist)

What I Got Wrong in a Decade of Predicting the Future of Tech (WSJ)

OpenAI Staffers Responsible for Safety Are Jumping Ship (Gizmodo)

OpenAI president shares first image generated by GPT-4o (VentureBeat)

Google I/O Is a Loud AI Warning Shot for Apple Weeks Before WWDC (CNET)

Chinese Robot Maker Creates Humanoid Robot that Can Do Almost All Human Tasks (TechTimes)

ChatGPT can talk, but OpenAI employees sure can’t (Vox)

As artificial intelligence creeps into every area of our daily lives, the world of sport is also looking for ways to harness its power. (Reuters)

7 Days In Incubator Longest Time Premature Baby Will Go Without Being Exposed To Advertising (The Onion)