This week, I am looking back at the best of 2022. Today it’s the four-part story of discovering my father’s unpublished novel.

1. The Past Speaks

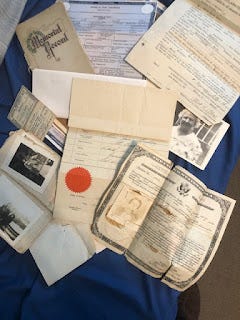

Squirreled away in one of my boxes of old files I found a portfolio of papers left behind by my father. It must have fallen into my hands in the days following his death from a stroke in 1999.

There’s a small notebook that he took with him when he joined the Army Air Corps in October 1942. He reported to Fort Custer in Michigan, the shipped out to Keesler Field in Mississippi, on to the Tech School Squadron in Chicago, and ultimately to the Aviation Cadet Center in San Antonio before going overseas.

Fortunately, he never saw action in the war. He did see the aftermath of war, however, in France and Germany, and as a stenographer at the war crimes tribunal at Nuremberg.

In the inside cover of his journal, he documented his promotions from PVT to PFC to CPL to SGT, etc. On the very first page is a faded B&W photo of his Mom, then one of my big sister Nancy (10 years older than me), then the first of many shots of our mother — mainly of her taking golf swings — plus his own three sisters, a 1930s car, one of his his brothers, two of his brothers-in-law, and some Army buddies and their wives and a few of him fishing.

He loved to fish.

He must have thumbed through this many, many times while away from home.

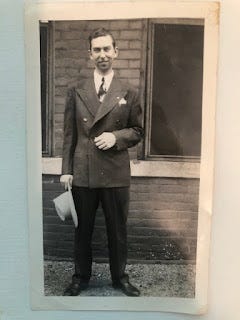

Although he told me stories about his life, I never was fully able in imagine what it had been like for him, born in 1916, growing up on a small farm in Canada, the youngest of six kids, losing his father at the age of ten, then leaving the farm with his mother to live in town (London, Ontario) for a short while, before on to Detroit as “nickel immigrants.”

Five cents was the cost of crossing the river on the ferry in the 1920s, and therefore pretty much the cost of citizenship in the USA — for those of the right European descent.

Because he was the youngest, it turned out that my father outlived all of hIs siblings, surviving just longer than his sister Norma, who passed away a year before him. Accordingly, he ended up with many of his siblings’ official documents — birth certificates, an application for citizenship in the U.S., a social security card, wedding certificates, photos, and finally, their death certificates.

Two of his sisters died with no other surviving relatives, so he became the sole custodian of their life chronicles.

What am I do with this stuff?

As far as I can tell, none of my Dad’s siblings left any writings behind to document their lives — no journals or letters, just a few faded photographs and those yellowed documents.

My Dad was another matter, however. Inside a manilla folder marked “Manuscript” he left a combination of handwritten and typed pages, apparently a short story or novel that he started to write. There are notes, an outline, and a certain amount of narrative.

If memory serves, this may be the story about a man’s escape into the north woods, where he survives on his skills as a fisherman.

Early in his story, there is this: “The world is divided into two kinds of people, those who must fish and those who can’t understand.” I haven’t read very far into the manuscript yet, but I believe a woman shows up with a great golf swing.

While the manuscript may never qualify as the Great American Novel, it will definitely be of interest to us, his descendants. And I’ll say this about my father — he would have made a hell of a contestant on that television series “Alone.”

2. A Shocking Turn

Reading further into my father’s old writings, which I wish I could carbon-date, but probably were created anytime from the 1960s through the 1980s, I discovered a shocking turn of events in what appears to have been his main short story, or attempt at a novel.

I should begin by saying that these pages seem to have been stashed haphazardly and probably were a project or projects he started and stopped over a period of years, perhaps decades. It is not clear to me whether the pages conflate several stories or fantasies, but I seriously doubt he ever showed them to anybody.

After he died in 1999, my mother asked me to empty his things into a box and take them away. She didn’t wish to go through them herself. This week is the first time I’ve ever looked at them carefully.

Anyway, the writing is very clearly autobiographical; he didn’t stray far from the contours of his own life. His main character “Joe” has a corporate job that he tolerates in order to support his family, a pretty wife he adores but perhaps misunderstands him, several lovely daughters he dotes on, and finally a son.

In real life that was his reality and the only son was me. But in the story he names the kid Tommy, after himself.

(By contrast, I was named after my father’s father, who died when Dad was only ten. So of course I never met the original David Weir, since I didn’t show up until some two decades after he passed away.)

I was sort of thrilled to find myself in Dad’s story, albeit in fiction, but quickly noticed that Tommy seemed to more like a figment of Joe’s imagination than an actual boy. The narrator describes what he thought Tommy might be like when he reached high-school age and expects him to be athletic. Of course in real life fathers often imagine the life their sons will lead when they’re small, so this didn’t seem all that strange.

Still, I had an odd sense of foreboding as I read about Tommy in the story. He never really seemed to be there.

I also was distracted by some of my father’s side notes, or annotations, describing ways this story (or stories) might possibly proceed. Sometimes the thread was about escaping his domesticated life into the wilderness; other parts just continued with the mundane realities of suburban life.

Partly I feared finding something dreadful, like a secret love affair or a crime that would have been a thinly veiled confession that I most certainly would not want to know about.

But there was only a passing reference to “an encounter w/Indian girl in the wilderness,” which was never explained.

Most of all, I was wondering how my stand-in Tommy would turn out. A star athlete perhaps? A successful journalist? A gallant leader of the community?

Well that turned out to be the really big shocker in the story.

Because one workday little Tommy just dies!

And I did not see that one coming.

Right about the age of twelve, he falls out of a boat, hits his head on a log and drowns in a lake. The little guy seems to have been out there on his own without Joe, who was at work.

Returning to reality for a moment, and trying not to take Tommy’s demise too personally, I remember a few incidents from my youth that might be relevant. On one occasion, my best friend Mark and I were horsing around in a motorboat and flipped it, casting us and all of our fishing gear (including my Dad’s) into the lake.

We limped home, somewhat chagrined, because it was a big deal to have lost that fishing equipment. But my Dad simply put on a snorkel and some flippers and went out to the spot in the lake, dove in and recovered his gear.

On another occasion, Mark and I were fishing in a cove at Ludington State Park when we discovered a dead man floating in the lagoon. The dead man had white hair like my Dad’s. That time there was nothing to be done about it.

Anyway, I was shocked that my father decided to kill little Tommy off in the story. I thought he was a likable little guy, plus it was such a dark turn. I always thought of my Dad as the ultimate optimist.

Still trying to process this tragic news, I kept on reading. The story goes forward without much looking back on Tommy at all, actually. As near as I could tell Joe doesn’t seem all that broken up by Tommy’s demise.

(Maybe my father took a break from writing the story for a stretch and when he picked it up again, simply forgot Tommy had died?)

Who knows. Anyway, when Joe vacations in San Francisco, tours Fisherman’s Wharf, and generally does the stuff that my Dad actually did with me in the 1970s, he seems carefree and content.

Soon after that, the story starts wandering off toward the sunset, so I have stopped reading it, for now.

***

P.S. When I told my oldest daughter about the tragic saga of little Tommy, she shrugged and reminded me of the fact that I almost died at about age 12 from an undiagnosed heart infection, and never really had a fully normal childhood after that. I couldn't play sports, for example, which my Dad had hoped for, and escaped into reading, fantasy worlds and writing instead. Perhaps this affected him in ways I never fully considered until now.

3. The Escape

This business of piecing together my father’s unpublished writings is getting complicated. As I figure out how to put the pages in order, and discover more side notes, outlines, and hand-written parts, I realize the whole thing ties together into a draft of what he envisioned would eventually be a book.

And that book was to be a semi-self-biographical novel about a man dreaming of escaping from his conventional life after a series of overwhelming personal tragedies.

Since I am sorting through this material daily, in between other responsibilities, I’m bound to make errors — some of them big ones — along the way.

Then I’ll correct them and keep going.

Yesterday I made a big error when I said that my author-father had named his son in the story Tommy. Actually, I now have discovered that the name he chose was Timmy. What threw me off is in the typed version it’s Tommy with the “o” hand-corrected to a “i” lightly with a pencil.

When I first saw it, I read straight through that pencil mark in two places and fell for the typo.

Freudian slip? Maybe, but if so by both me and him, assuming he was the typist.

Anyway, Timmy still dies in the story, but so does another major character.

Joe’s wife, Helen. This was another shocker for me.

(Dad, you’ve got to be kidding! Mom gets killed off too?)

What kind of novel is this?

I haven’t located the explanation for Helen’s demise yet, but there’s a long section where she is utterly inconsolable over Timmy’s death. Soon after that we learn she’s gone.

Part of the issue here is Dad’s papers when I found them were badly out of order, some numbered, some not, as if they had been stuffed away in the middle of a move. So I got easily confused.

Near the bottom of the pile of pages, Helen and Timmy are suddenly alive again. Joe is 45, Helen 39, and their beloved daughter (maybe named Julie?) lives out in L.A. and had a daughter of her own, who sounds quite delightful.

I also learned that Timmy was quite a delightful child as well. He was full of energy, walking, running and talking at exceptionally early ages, always falling down and getting up again, keeping going, though his head was usually “black and blue.”

Sounds like he was mistake-prone.

There is a parallel story developing at Joe’s office, where an important guy named John T. Lewis — later corrected by pencil as Joseph T. Gallagher — shows up and is making a serious presentation when an interruption comes in the form of a phone call.

Gallagher can barely control his anger at this disruption.

This turns out to be the frantic phone call that Timmy has died ( once again), which apparently irritates Joseph T. to no end.

(This whole saga is starting to remind me of a Bob Dylan song where the only order is disorder. I like Bob Dylan songs.)

The business section of the novel is pretty boring, to be frank, and has to do mainly with failed attempts to acquire various other companies.

But I might understand more about the overall arc of the narrative if I could force myself to read a long, long, long section where a whole bunch of the main characters engage in an incredibly well-documented round of golf.

There’s some guy named Mort, another one called Bill, and so on. Helen is there as well with her beautiful golf swing. The score is tied at some point, and there’s all this detail about tees, playing through, putting and the mechanics of the game of golf, which I confess never has been able to stir the depths of passion in my soul like it clearly did for my Dad.

It’s charming if it’s your thing, I assume.

Maybe some answers as to what this is all about are buried in the rough in there, such as Helen getting a big hole in one, or getting hit in the head and killed by an errant shot from Joseph T. Gallagher.

(Maybe I’ll get around to reading it soonish.)

Anyway, after Timmy and Helen died, Joe starts plotting his secret escape into the wilderness. Using a false name, so he couldn’t be tracked, he charters a flight somewhere deep into the mountains, where he is going to conduct a mysterious scientific experiment…

But I don’t understand why it has to be a secret.

4. The Island

Digging further into my father’s papers, I have now learned significant details about the tragic end of his wife Helen, aka Mom.

After their only son, Timmy (aka me), drowns in what Joe dismisses as a “stupid boating accident,” Helen goes into a deep depression, starts “hitting the bottle,” and finally drives her car off a cliff, killing herself.

Holy crap.

Okay, so she committed suicide.

But I should note that my father made a side note at this point in the manuscript to remember to devote a chapter describing how hard it must have been on her being alone at home, trying to cope after Timmy’s death, with him back at work.

Such dramatically tragic events never occurred in our real family, of course. But my mother did have an extended period of emotional distress when we relocated to another city due to my Dad’s transfer and this coincided with my boyhood illness as well.

During the worst of that stretch, I remember trying to console my mother. She cried a lot. My Dad worked a lot.

The heart infection I experienced went undiagnosed for two years, doing its damage, after our family doctor told my Dad (with me sitting right there), “It’s just psychological — it’s all in his mind.”

My Dad believed that. I remember him telling me as we left the office that I was “weak” and “lazy” and should just stay home “with the girls.”

I didn’t blame my Dad for that assessment because I believed it too. Back in those days, the 50s and early 60s, nobody said stuff like “trust your body.” So why else did I feel no energy to chase down a fly ball (I was dismissed from the Little league team); and why did I just want to spend most of every day lying on the couch or drinking tea with my Mom and sisters?

It must have been all in my mind.

But I knew I wasn’t weak, actually. I felt that if I wanted to, I could run faster than any of the other boys. On the other hand, I did suspect I was lazy.

Meanwhile, I really liked what seemed to be in my mind. It was on fire with ideas, fantasies and the worlds that books suggested to me. I read loads of library books, invented fantasy sports leagues, composed articles for a “newspaper,” kept elaborate statistics for the imaginary players, and generally was living a richly passive life rather than the physically active life my father wanted for me.

When it finally turned out that I had indeed been seriously physically ill the whole time, and had to be hospitalized with pneumonia in very bad condition, nearly dying, my father must have experienced an awful wave of the kind of guilt that is difficult to bear, let alone talk about.

He had been misled by an authority figure and had almost lost his son in the process. Actually, as it turned out, he did lose me, in some senses.

But in the process he probably helped to create an investigative reporter.

And although he never would have admitted it, my father was probably every bit as sensitive a man as I was. He just never had the language to express that kind of thing.

With me, he tried to hold to his idea of what a man should ideally be, based on the way it was when he grew up, albeit absent his own father, who died when he was ten.

In our most intimate moments, he confided to me how he had never imagined how disgusting and gross other men could be until he went into the military. There, he witnessed sexist and racist things that turned his stomach, according to what he told me.

But then sometimes he seemed to try to pass some of those those awful things on to me, like commenting on the way certain girls’ bodies looked when he caught me looking at them. This was thoroughly disgusting and I hated him for it, but in a way it never really felt like it was really him talking.

As the probably over-sensitive, impressionable boy I was, his many stories turned me firmly against male culture and military service long before the Vietnam War gave me the excuse I needed to burn my draft card, renounce U.S, imperialism and get arrested in demonstrations.

I just never wanted any part of that gross side of men. By then I preferred, by habit and nature, the world of women, although they too quickly proved to be way too much for me emotionally as well.

So I guess I became a man without a comfort zone. Sort of like an island.

***

Alas, I digress. Back to my father’s story, the one he never published.

After his wife Helen’s dramatic suicide, which I imagine would have resulted in at least a small news report, Joe puts in for a leave from work, and makes an elaborate plan to travel deep into the wilderness. I’m not sure where this was, exactly, but it probably was somewhere in Canada or Alaska.

We learn that Joe makes lists of everything he will need, hires charter pilots, and hikes deep into the area until he finds an island with a narrow gorge leading to a perfect swimming hole and granite steps up to the mouth of a mysterious cave.

As near as I can tell, Joe’s goal is to prove to himself that he can survive under difficult circumstances in the wild, fending for himself, while exploring virgin lands, or conducting mysterious experiments, or seeking some sort of closure before returning to his humdrum workaday life.

He’s trying to get over some very hard stuff, but he’s excited.

Among Dad’s papers is a drawing of the area where Joe seems to have at least temporarily found what he was seeking.

And I hope that he did.

(End of story.)

NEWS LINKS:

US to require travelers from China to show negative Covid-19 test result before flight (CNN)

Japan launches new restrictions for travelers from China (CBS)

After years with little covid, videos show China is now getting hit hard (WP)

‘Unfathomable restrictions’ on women’s rights risk destabilizing Afghanistan; Security Council voices deep alarm (UN)

UN Security Council urges Taliban to reverse restrictions on women (BBC)

‘Sense of helplessness’ for Afghan women on Taliban NGO work ban (Al Jazeera)

Afghan lecturer despairs over education ban (Reuters)

New sanctions starting to bite Russia’s economy as Moscow admits deficit impact (CNBC)

A flood of Russians arrive in Uzbekistan to avoid being drafted and sent to Ukraine (NPR)

Not Now, Europe. Second War Threatens to Explode (Daily Beast)

Tesla Stock Heads for Worst Performance This Year of Any Major S&P 500 Company (WSJ)

Southwest’s Debacle, Which Stranded Thousands, to Be Felt for Days (NYT)

Former WH aide says Trump allies helped deliver a ‘dolly of boxes’ full of what may have been classified intelligence documents to the Situation Room in the final days of Trump’s presidency (Insider)

Architect of Mich. governor kidnap plot sentenced to more than 19 years in prison (WP)

Pence spokesman says document showing FEC ‘filing’ is fake (The Hill)

Rep.-elect George Santos poses a serious risk to the GOP (CNN)

G.O.P. Leadership Remains Silent Over George Santos’s Falsehoods (NYT)

‘The closest humans come to being a fish’: how scuba is pushing new limits (Guardian)

Neanderthals Were Smart, Sophisticated, Creative—and Misunderstood (Newsweek)

Terrawatch: the rise and bigger rise of Mediterranean sea levels (Guardian)

The Tech Companies That Wield Even More Power Than Facebook or Google (Slate)

New Pam Ad Campaign Reminds Teens That Pam Can Get Them High And Is Easy To Obtain (The Onion)

No comments:

Post a Comment